Manoj wasn’t the kind of participant who was going to share a lot. On this Tuesday morning, we (a design research team) had settled in his shop in Bangalore, India, to do a contextual inquiry, but the subject of our inquiry made him anxious: how small business owners deal with payments.

From earlier conversations with Manoj, I knew that his challenges were many given that he was working in an emerging economy that lacked resources. As a small business owner, he was trying to establish himself in the market, with plans to expand so he could provide for his growing family. With a third baby on the horizon, his immediate worry was his increasing expenses.

Also, Manoj was facing real-time challenges during this research session: 1) he was struggling to comprehend the English language of the prototype; 2) he was concerned about his mobile data usage in downloading screens: and 3) he was uncomfortable with some money-related questions.

At one point, I asked Manoj about connecting his bank account to a payments app. He hesitated and then gave a rather superficial answer: “I don’t like it, I’m not that kind of person,” he responded.

What followed next was silence. Sensing his discomfort, I wanted to move on to the next question. But I waited.

A few seconds. And a few more seconds. And then, Manoj spoke:

“I am afraid. What if my bank information gets stolen? There are hackers, you know. I’ve heard of people whose bank accounts got drained overnight.”

“And you feel that way because ….” I intentionally left my sentence incomplete.

Manoj began to talk more about his concerns around security:

“I want security to be hard and fast. I don’t want the government to log into my account. You need to show me that my money online is as secure as my cash is with me. I think if it’s somewhere online, there are hassles regarding security breaches. My cash is mine. It’s in my pocket. I don’t have to be worried about security issues.”

We continued talking for another 40 minutes. At the end of it, we had a tacit understanding of Manoj’s needs. We had an idea of how our team could improve the product based on his feedback.

Listening

Sometimes we don’t really listen. We listen just enough to get by in conversations. Listen enough to find a point that we can say in a meeting. Listen enough to find a commonality so that we can share our own stories. Listen enough to get a signal to get our work done.

But as a user experience researcher for Google, Microsoft, Flipkart, LinkedIn, and Intuit, I’ve learned that that is not really listening. I’ve spent years conducting hundreds of interviews with participants to uncover how people think about a product and how their real-life context impacts how they use a product. Listening is a skill that has to be learned and practiced because it forms 90% of a researcher’s conversations.

Here’s what listening looks like to a researcher: Listening creates a space — a space for participants to open up. This empowers us to understand how they feel and what it’s like to see the world through their eyes.

Conversely, when we don’t listen, we close ourselves to learning. We fail to establish a rapport with our participants. This in turn holds them back from going deeper and we miss out on unpacking their behaviors, motivations, and friction points when using our product.

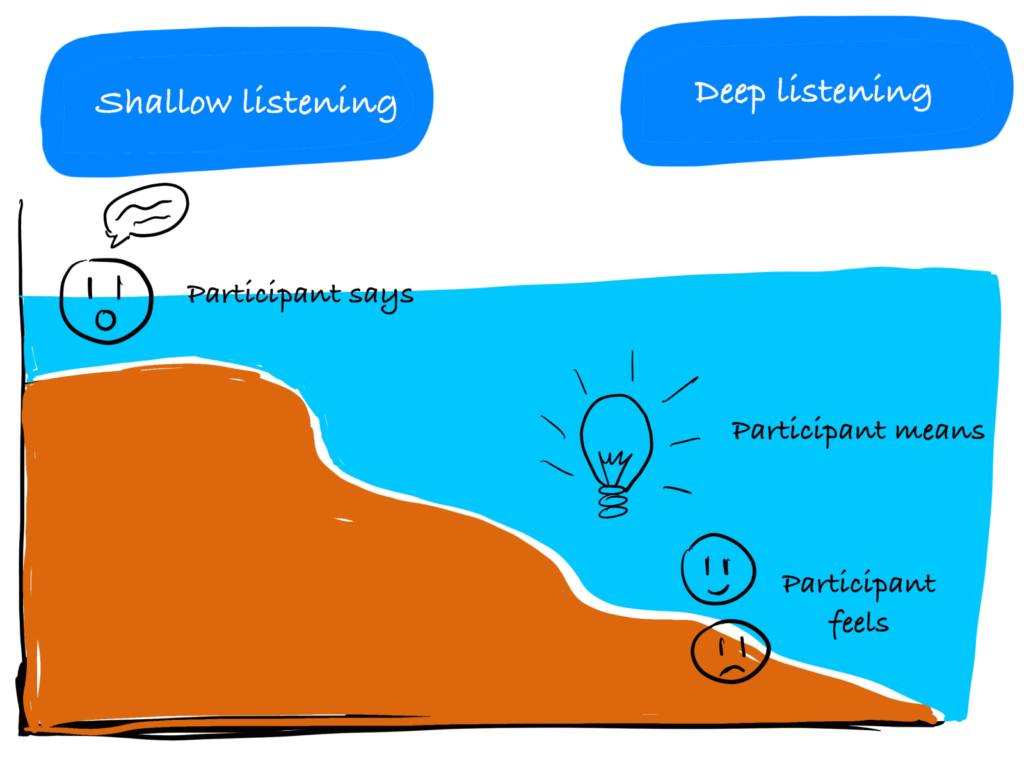

Shallow vs. deep

When we listen in a shallow mode, we project our biases onto the other person. We miss glancing into differing perspectives because we are too busy validating ours. Deep listening helps us put ourselves in other people’s shoes and enables an understanding of their cultural backgrounds that might have shaped who they are, their attitudes, and behaviors.

In the story above, if I were listening to Manoj at a shallow level, I would have failed to uncover his unique experiences growing up in an emerging economy. I could’ve biased his growing up to be similar to mine since I come from similar cultural roots and have grown up in the same social fabric. But deep listening exposed me to challenges in his life as a small business owner, entrepreneur, father — and a person with insufficient English fluency who wanted to limit his data-usage.

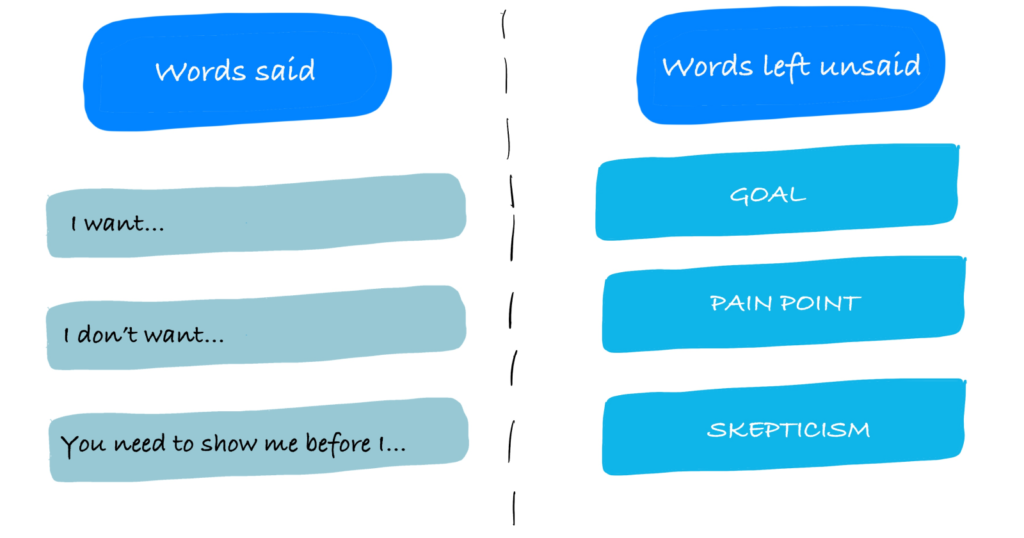

Literal meaning vs. observing word choices and underlying emotions

The words people use tell us a lot about their beliefs and values. If I hadn’t focused on Manoj’s choice of words, I’d have walked away feeling baffled and confused about his real worries — is it government, is it non-cash instruments, is it hackers, or does he have a problem with online platforms in general? Listening to Manoj’s choice of words brought home the realization of a lot of things which were left unsaid:

- He was very afraid of giving his bank information online.

- He was skeptical that an online platform can be secure enough.

- He believed in the possibility of the government peeking into his bank account.

- He was sure that his money was absolutely safe with him in the form of cash.

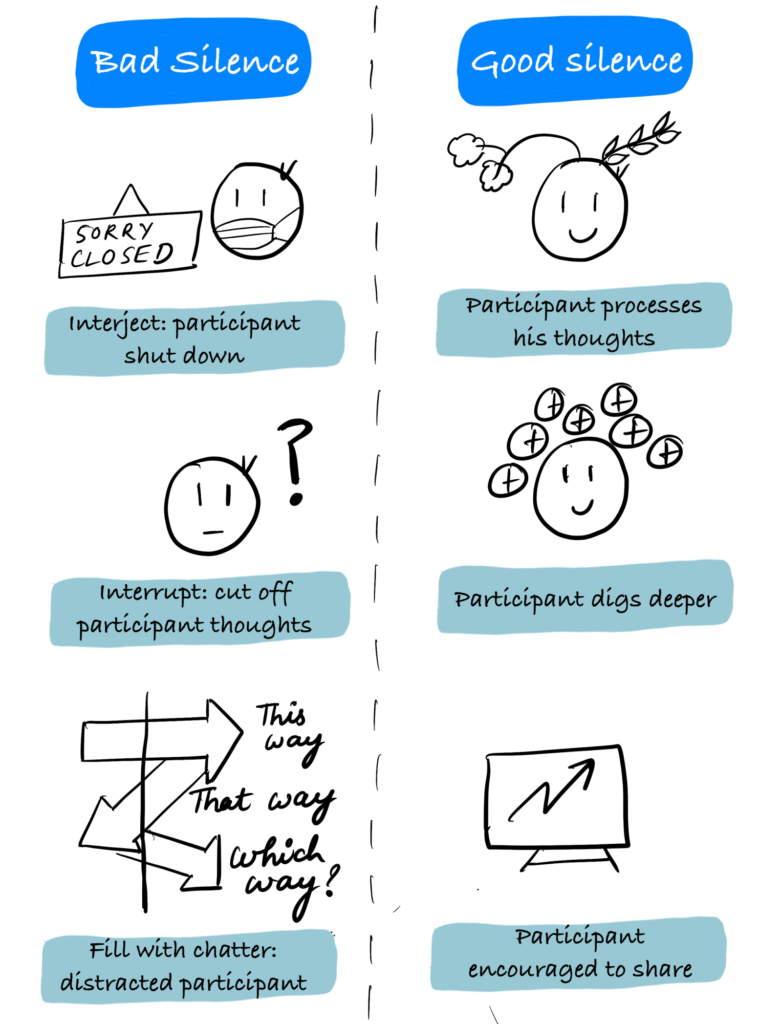

The value of intentional pauses

Pauses create space for the other person to process their thoughts. Keeping quiet can be a powerful technique for eliciting thoughtful responses. In the example above, if I had moved to the next question to fill the uncomfortable silence after Manoj responded with the superficial answer, ‘I don’t like it, I’m not that kind of person,’ then Manoj might have simply moved on from what was being discussed and discontinued his thought. Instead, a pause got him to offer a valuable insight regarding his security concerns on online platforms.

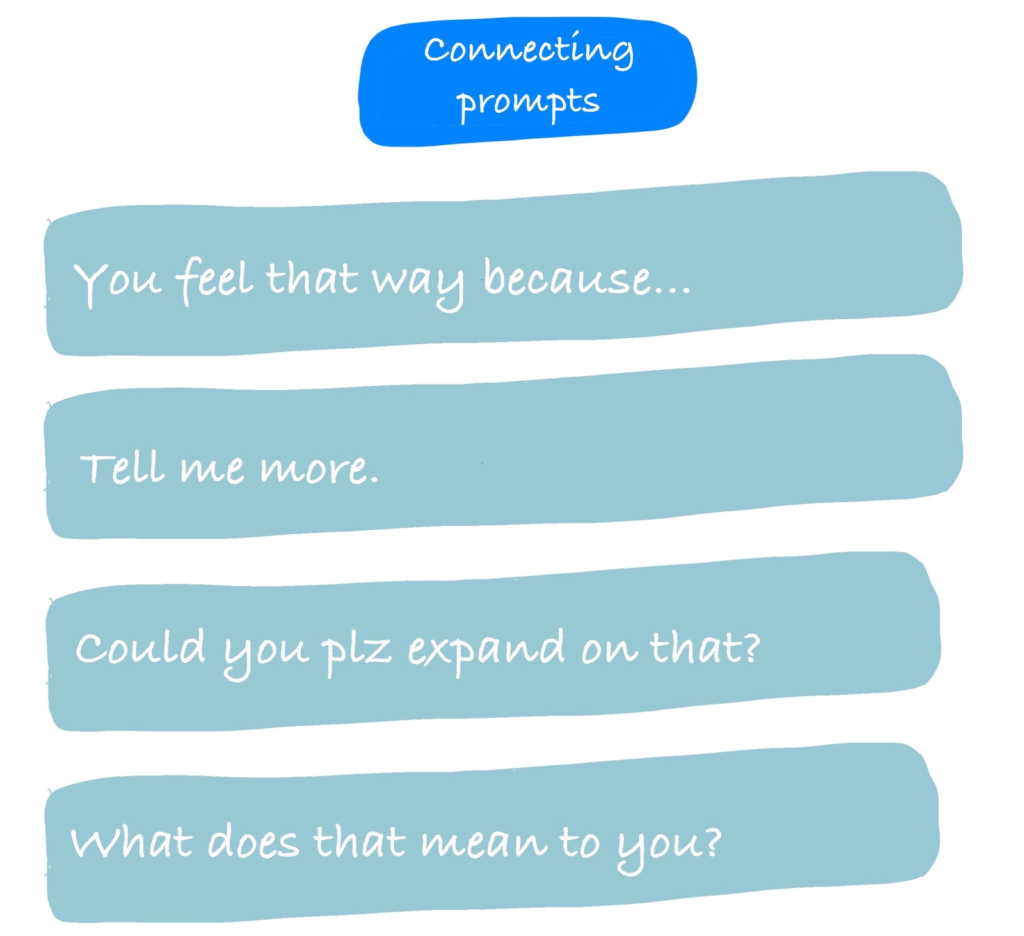

Closing conversations vs. offering connecting prompts

Prompts help us deepen the conversation without pushing the participant too far. In the story narrated above, as soon as I saw Manoj open up a little, I offered a nudge to encourage him to keep going. “And you feel that way because …” was gently inserted so he could expand on his feelings. If I hadn’t nudged him, he might not have felt safe to release the fears and skepticism he carried.

If I had asked him a yes-no question instead such as, “Does it mean that you don’t like online payment platforms?” all I’d have gotten would be a single word response: no. At this point I’d have closed Manoj further to talking about a sensitive area that he was already reluctant to address.

Listening creates a space — a space for participants to open up. This in turn empowers us, as researchers, to understand how they truly feel and what it’s like to see the world through their eyes. Conversely, when we don’t listen, we close ourselves to learning. We fail to establish a rapport with our participants. We fail to unpack their behaviors, motivations, and friction points. We fail to go deeper with them.

To become listeners who connect with strangers and establish a rapport to unpack specific insights — the insights that ensure that our product is useful to the target audience — we need to distinguish how we might be listening vs. how we can listen better. We have to lean in and listen on a deeper level to what’s being said — and what’s left unsaid. With deliberate effort, we can become better listeners and truly understand and empathise with others.

Apart from being a strong voice for user-centricity, Anshul believes in a person’s inherent potential and has written a book on overcoming the fear of failure.