As designers, we put so much thought and care into our designs before they go out in the world. Once out in the wild, our designs are used by people who don’t always behave the way we expect them to. Sure, they’ll comment in a customer interview that they’ll do this and that — but people (including you and I!) are irrational and will tell you what we think we will do. They are not always reliable in sharing what they actually do.

One field of study that has helped me with this problem is behavioral science. I started learning behavioral science in an Irrational Labs bootcamp. One of the most straightforward ways to apply behavioral science in design was using the 3Bs. (We’ll get into “the how” in a bit.) As my team and I did this, little by little we started to hear from our customers that they were more clearly recognizing the benefits of our product.

At Intuit design is at the core of how we approach real life customer problems and solve them in a meaningful way for people. Using behavioral design and applying behavioral science can help to enhance the user experience and make it easier for customers to understand and use the features and benefits of your products. By considering how people think, feel, and behave when interacting with your products, you can design features and experiences that are more intuitive, engaging, and effective.

By applying behavioral science, you can create solutions that meet their needs and add value to their lives. To create meaningful and effective solutions, you can help your customers make better choices and achieve their goals.

How do I start?

The secret to adding behavioral science into your designs is the Bs framework:

- Pick a behavior

- Minimize any barriers

- Amplify the benefits

Let’s look at this framework in more detail and at some examples of how it works.

Pick a behavior

What is the key action that you want the user to take? The more specific and measurable the focus, the better. Avoid vagueness and get “uncomfortably specific” by defining what they should do and when they should do it.

An example

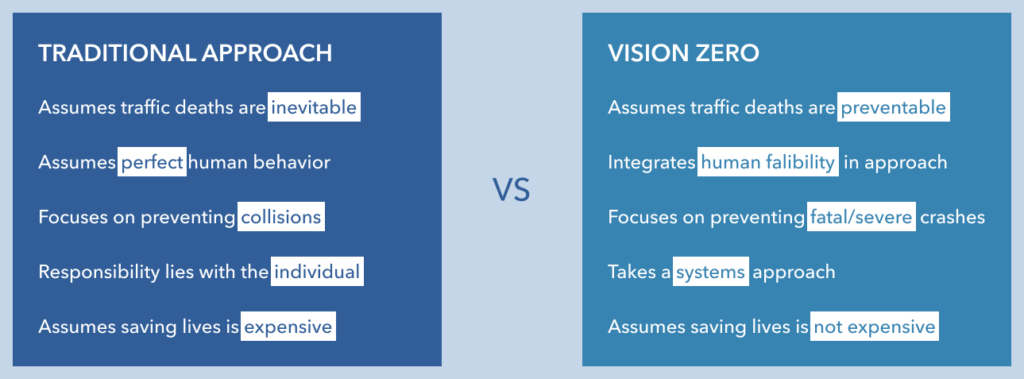

A Swedish-born initiative called Vision Zero focused on reducing automobile collisions caused by human error. Over a ten-year period, they reduced fatalities by an astonishing 90%. Part of their success came from picking the key behavior for road safety: getting cars to slow down. Installing roundabouts and narrowing roads caused drivers to reduce their speed which led to fewer fatal collisions.

Reduce barriers and friction

Barriers can increase friction with our customers and prevent customers from doing the things we want them to do. Some examples of barriers include having too many choices, forgetting a password or unclear instructions. When we design for behavior change, we look for opportunities to reduce those barriers with our customers. Choices can be hard for our customers, but we can help make deciding easier for them. With behavioral science, we can design things so that it’s much easier for them not only to do the things, but also make good choices they are happy about.

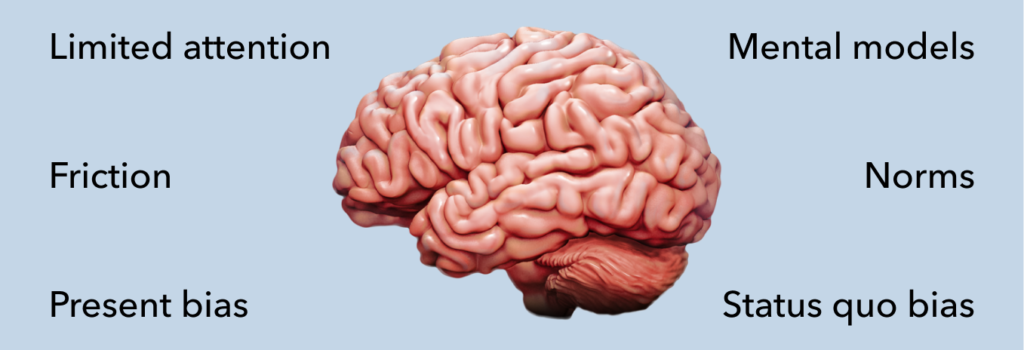

Here are some examples of barriers to solve for:

- Limited attention: We can only focus on a limited number of things at a time.

- Friction: This can include having too many options, or a complex choice which can lead customers to opt out of taking action.

- Present bias: People often value what’s now instead of what’s in the future.

- Mental models: Our understanding of the surrounding world can bias our actions and behaviors.

- Norms: Our understanding is influenced by what others think is good. We behave similarly to those around us.

- Status quo bias: We can bias towards the present and see a change from the status quo as a loss.

Volkswagen’s “fun theory” campaign offers an example of reducing barriers to make the desired behavior easy and appealing:

What was once a barrier — the effort of taking the stairs as opposed to the escalator — is made delightful through the “fun theory” campaign in Stockholm. People are encouraged to take the stairs instead of the escalator using interactive piano stairs. And thanks to this project, 66% of the people who passed by the original project site chose to take the stairs over the escalators.

Another way to reduce friction is through thoughtful choice architecture, which is the area of design focused on different ways in which choices can be presented and organized to help people make better decisions. A good example of this is the placement of healthy snacks at eye level on the shelves, while placing unhealthy items in harder-to-reach locations. This arrangement makes a healthy choice more likely. When properly applied, it is good design and design for good, something that helps the customer in a way they will appreciate and help them make better choices.

Amplify those benefits

Benefits motivate customers to take action. Amplifying benefits — at the right time and right place for our customers — increases the drive to complete a behavior.

Key benefits that we focus on:

- Immediate (in the moment): The closer to now, the better.

- Concrete: In order to get our users to perform the proper (and desired) behaviors, we need to give them very specific instructions.

- Hedonic: This is the pleasure motivator. (Think sinfully delicious chocolate.)

When amplifying benefits, ask yourself:

- What would impact a customer’s life right now?

- Is the benefit obvious and concrete?

- Does the benefit appeal to someone’s emotions?

An amusing example is found at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. The cleaning manager was trying to reduce “spillage” around the urinals. He settled on etching small, photorealistic images of flies on the urinals, right near the drain, turning a mundane thing into something game-like. This, in turn, resulted in an 80% reduction in urinal spillage. It’s interesting to see how the use of game-like elements, such as the fly decal in this case, can be effective in influencing behavior and achieving desired outcomes. By adding a fun and engaging element to a task that might otherwise be seen as mundane or unpleasant, it may be more likely to capture people’s attention and motivate them to engage in the desired behavior. The result of this was that this little fly resulted in an 8% reduction in total bathroom costs!

Behavioral science at Intuit: Making taxes satisfying

Nobody loves getting their taxes ready. It’s a pain and it takes time and a lot of mental energy. So, how does TurboTax turn dread into delight with behavioral science?

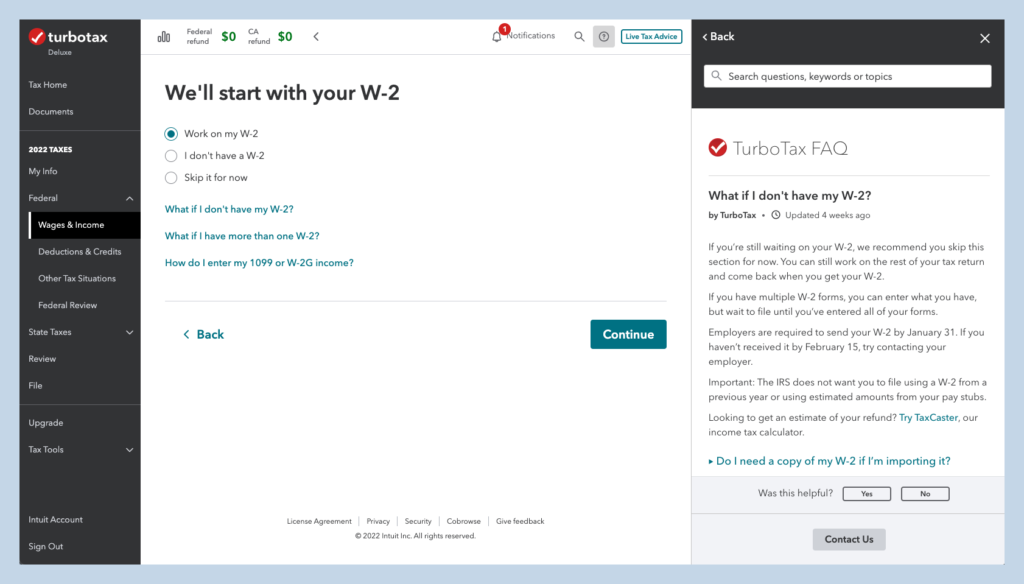

By keeping it simple with a combination of smaller steps and instructions. They gently guide customers to the concrete benefit to complete the behavior we want them to do. Providing the right information at the right time reduces mental strain and decision fatigue. We all need a little pat on the back, so TurboTax acknowledges those key steps with celebration moments. Along the way, customers can see the immediate benefits of using TurboTax as their expected refund updates throughout the process.

TurboTax hits all of the 3Bs:

- Picking a behavior: Get customers to complete tax details.

- Minimizing barriers: Reducing the friction by making small and specific tax tasks to get done.

- Amplifying benefits: With specific concrete instructions and providing confidence with success celebration messages when complete. Give our customers that virtual pat on the back for a job well done.

And they use those 3Bs to give customers 100% confidence that they’ve got this. The Turbotax experience reduces friction by providing smaller focused tasks along with relevant support content.

Behavioral science at Intuit: Instant Karma with Credit Karma

It’s no secret that people have a hard time saving money. And an even harder time turning saving into a habit.

Credit Karma cleverly triggered the saving habit with instant karma. Customers using the Credit Karma Debit card are incentivized to win $20K when they save $1. They’re sent a message and with one click, they have the potential to win prizes for savings.

They make it easy to start saving with a small amount, but with an additional bonus to win. It’s a very small cost, barely a barrier. They time the sending of this message for the end of the month, when people are thinking about saving more, and put it in the right place where it’s easy to opt in with a click.

Here’s how Credit Karma uses the 3Bs:

- Picking a an uncomfortably specific behavior: Saving money as a habit

- Minimizing barriers: Present bias refers to the tendency to place a higher value on immediate rewards or costs, compared to future rewards or costs. This can lead to a preference for immediate gratification, which can make it difficult for people to make decisions that involve delayed gratification or long-term planning. By highlighting the potential future rewards of saving money at the end of the month when they typically think about saving money, it may be possible to motivate people to prioritize saving and to think more carefully about their spending habits.

- Amplifying benefits: By tapping into the hedonic delight of winning money. With the incentivization of savings and a better than average chance to win money.

The results increased brand trust, which in turn led to more use of the Credit Karma debit card. Customers saw their credit utilization go down and their credit scores go up. All part of Credit Karma’s larger objective: helping people spend responsibly.

Apply behavioral science to your designs

Want to start using behavioral science in your designs? Here’s where you can learn more:

- Podcasts

- Books

- Course