Sewing as a skill, art form, and craft has been omnipresent yet elusive to me for forever. My mother, a proficient second-generation seamstress, raised my three sisters and me in matching handmade dresses. Despite my mom’s best intentions, I never learned the craft as a child. My traits of perfectionism and lack of patience were constant barriers to nailing the fundamentals required to learn the skill.

Fast forward to the spring of 2022 when I stumbled across a powder blue vintage Singer sewing machine at a neighborhood estate sale. It came complete with all the accouterments: spare buttons, metal zippers, candy-colored bias tape, and a motherload of vibrant unused fabric dating back to the 1960’s. 2022 would finally be the year I’d learn to sew.

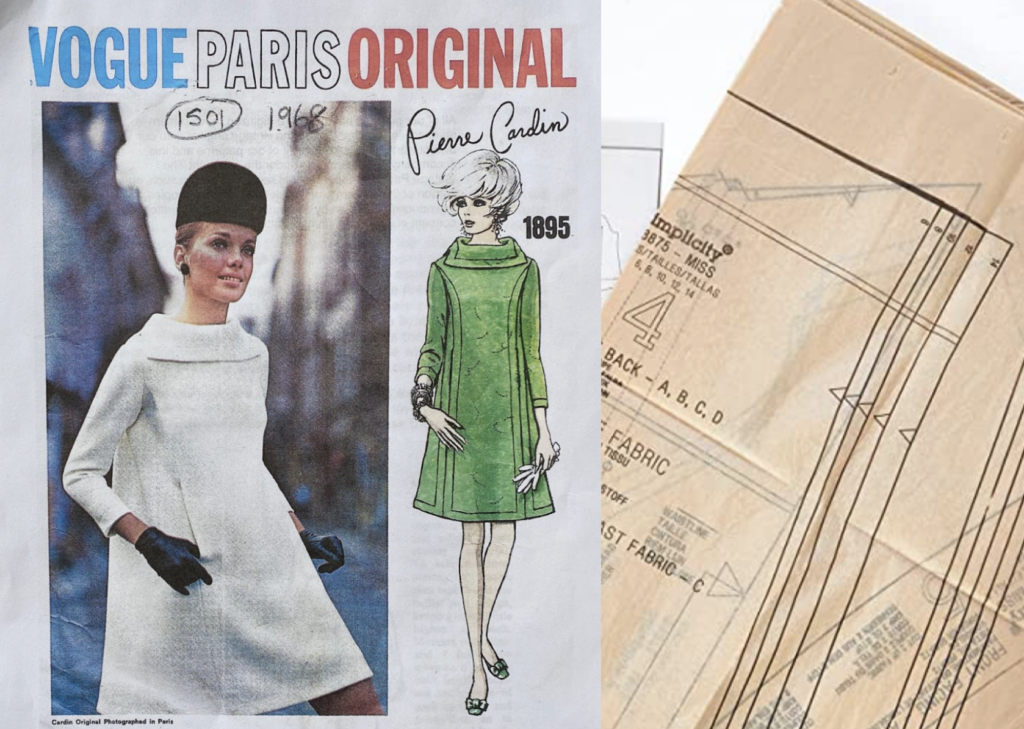

I knew what I wanted to make first – an emerald green Pierre Cardin overcoat – and I’d have it made in time for winter. As I unfolded the delicate sewing pattern, I felt a familiar surge of excitement, dopamine, enthusiasm, hope, and anticipation.

However, those feelings didn’t last. It wasn’t long before I realized that:

- I had no idea how to work a sewing machine nor how to troubleshoot it when something went wrong;

- I could neither read nor interpret a sewing pattern;

- I had literally zero technical skills.

I had unwittingly plunged head-first into a phenomenon called the Dunning–Kruger effect.

The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias of over-estimation. Dunning and Kreuger found that people with limited ability, expertise, or experience in a particular skill (or area of knowledge) tend to overestimate their competence in that area. Add to this the “novice’s curse:” the tendency among beginners in any skill or art, to move past the fundamentals too quickly and on to more elaborate, more sophisticated movements, skills, or techniques.

At the time, I didn’t see that this was happening to me. I’m embarrassed to admit this, but at home there’s a “pile of shame” sitting in my craft room. They are finished dresses that are so poorly constructed, they are unwearable and will never see the light of day.

But it’s not all doom and gloom—this experience served me in more ways than one.

- It forced me to make peace with where I am (that is, nowhere near the skill level required for that jacket). I’ve recalibrated my own expectations and have shifted from attaching myself to the outcome and getting frustrated to finding joy in nailing the fundamentals.

- It illuminated a connection between my hobby and my professional self—and inspired this article!

It might be hard to see the connection because, we’re talking about beginners here. What could a community of expert product designers learn from the novice’s curse? Because, despite the root cause, the pain is universal. How many times have we, as experts, felt the frustration of realizing what we’ve dreamt up is at odds with what is possible to build?

I’ve learned from my hobby that for the novice, limitations are commonly due to a lack of skills and practice. I’ve learned from my professional experience that for the expert product designer, limitations are often a nuanced cocktail of customer needs, available technologies, time, and pressure to deliver business outcomes. The limitations are different, but the goal is the same.

My goal as a novice was to dance through winter in a me-made wool coat. Ultimately, that vision is what forced me to find joy in the fundamentals. Our goal as designers is to define an ideal state that promotes what’s possible, what’s inspiring, and what’s, borderline unachievable. Then we must make peace with where we are at this moment in time. What are the customer needs, available technologies, and time constraints? Once we’ve made friends with our limitations, we’re free to create an inspired, well-designed, complete MVP that nails the fundamentals.

For example, take the set of placemats I made for my sister last summer. Having already made friends with my limitations (skill), I declared that the goal of this project was simply to practice the fundamentals. Because I lowered the goal to match my skill level, I was free to take my time and enjoy the process. I ended up with a set of four tidy, well-constructed placemats that I was proud to present as a gift.

In my work as a product designer, the same thinking applies. When I’m working on a new design challenge, the first thing I do is go get cozy with the limits. What are we solving for? Who is the customer? Where are we organizationally? What are we capable of realistically building right now? How soon do we need to deliver the solution?

With this context, I have a baseline that can serve me in two key ways:

- It tells me exactly where to push and provoke new thinking in any ideal state or solution I recommend.

- It informs the first meaningful thing I’ll deliver first.

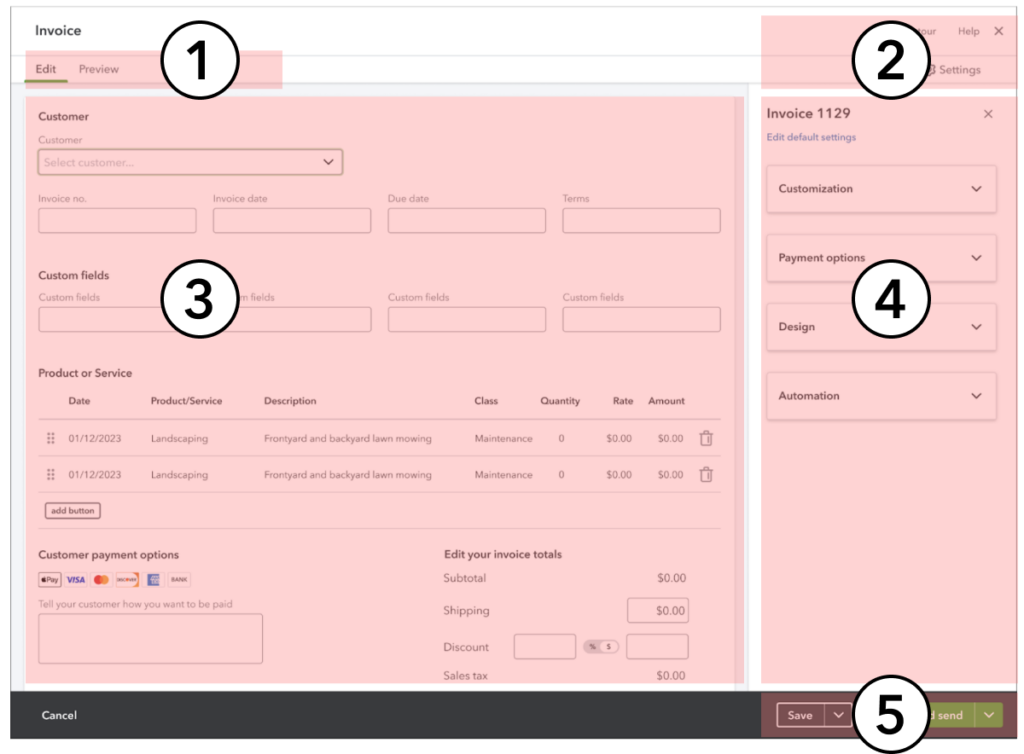

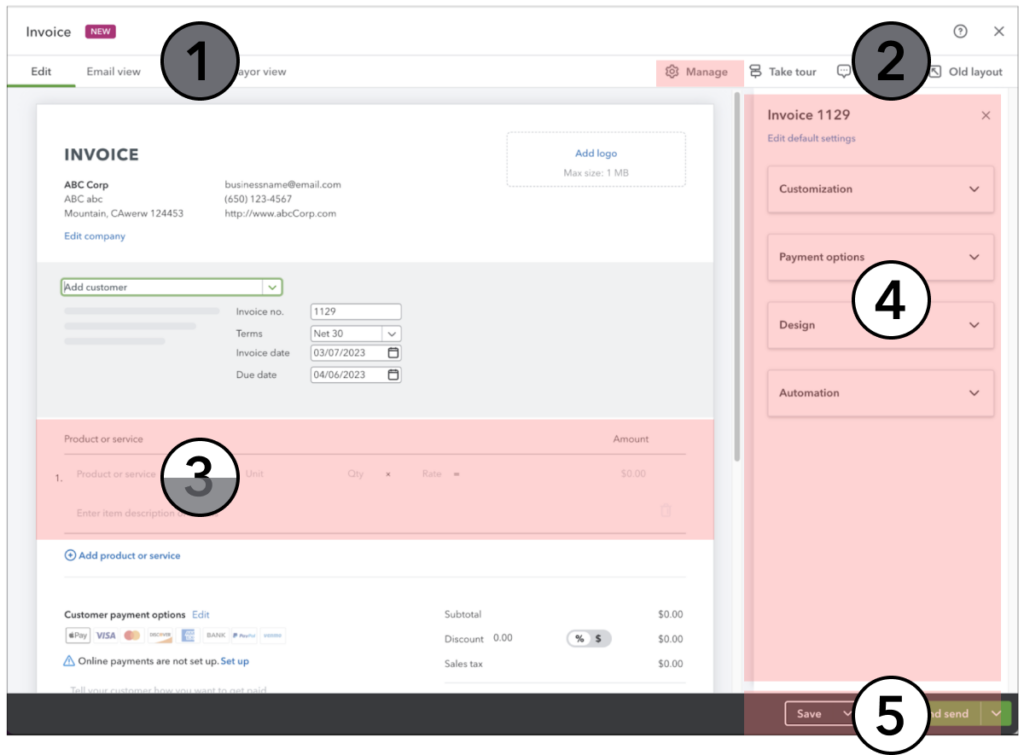

For example, I’m currently part of a team that’s focused on delivering a large experience refresh and technical migration.

Our ideal state includes all the bells and whistles: a visual refresh, animated transitions, a complete information architecture overhaul, and more. I’m grateful to have a baseline understanding of our limitations because it’s helped me guide the team to deliver a provocative ideal state that was inspired yet tethered to reality.

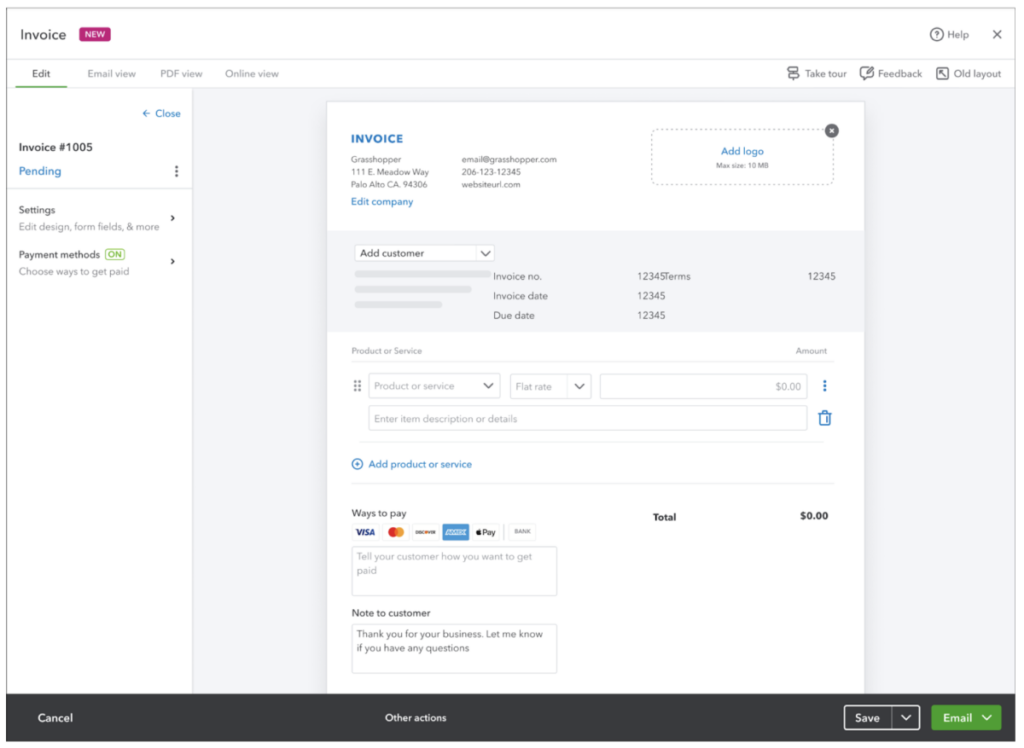

With the ideal state in hand, it was easy to carve out the small and meaningful first step (or MVP). Together we decided to focus on the interaction architecture first because it hit the sweet spot: it solved the customer problem, was technically feasible, and was design-system friendly. The icing on the cake was that this limited solution put us closer to achieving our ideal state.

Over the years, I’ve developed some better ways of approaching a project. I’ve found that developing this awareness makes all the difference between creating an MVP that’s a frustrating shell of what you initially imagined and an MVP that takes a meaningful step toward your vision (and one you can be proud of!).

| SEWING | PRODUCT | |

| Recalibrate my expectations | Do I have enough skill to make this complex jacket today? If not, what can I make today that will help me master the fundamentals I need in order to get there? | Is the technical infrastructure in place for me to deliver a visual design update along with the product fix I’m recommending? If not, what do we need to build today in order to get there? |

| Take pride in the fundamentals | I may not have made that complex coat yet, but I can take pride in the set of placemats I made for my sister last summer. The fundamentals were perfectly executed. | My team may not be able to launch the ideal state experience I designed, but in this cycle, we can launch a customer backed, design-system compliant information architecture update. It’s not all the bells and whistles, but it’s a beautiful and complete element of the ideal state that yields immediate customer benefit. |

Whether you’re learning a new craft or designing a product experience, it’s essential to make friends with your limits and work with them.

As a novice seamstress, I’ve learned to accept that my lack of skill has kept me from immediately creating my vision. But I recognize the importance of knowing where I want to be in comparison to where I am today. These days, I take pride in moments when I nail the fundamentals, such as sewing a pair of perfectly constructed bell bottoms for my daughter, or installing a zipper on the first try(!!!). I relish small, but meaningful steps that demonstrate I’m building skills that will get me to where I want to be.

In my work as a professional, if we have defined an inspiring, borderline unachievable vision and then gone on to create an MVP that masterfully balances where we want to be with what we can build today, there is nothing, NOTHING I’m more proud of. As cliche as it may sound, the journey is just as important as the destination, and the pride you feel in your progress and accomplishments along the way makes it all worth it.

The serenity prayer for product design

Accept the things I cannot change

This problem has been solved in QuickBooks somewhere SO for the sake of usability and continuity, lift and shift.

Have the courage to change the things I can

This problem has been solved in QuickBooks somewhere already, BUT the solution could use a refresh or an extension SO for the sake of usability and continuity, lift, shift, refresh, and contribute your shiny new, improved solution back to the QuickBooks design system.

Have the wisdom to know the difference

This problem has been solved in QuickBooks somewhere already, BUT I unwittingly delivered a novel solution that risks confusing customers SO for the sake of usability and continuity, go back to Step 1 or 2.